Project Densification Saves How Much Farmland?

By Mark Smith

In California’s agricultural San Joaquin Valley, real estate development has an insatiable appetite for … farm land. The American Farmland Trust’s report Saving Farmland, Growing Cities places aggregate population growth and farmland consumption into perspective

The population of the San Joaquin Valley, now roughly 4 million, is expected to more than double by 2050. At the same time, if the Valley keeps developing an acre of land for every 6.4 people, the amount of land available to produce food will shrink by at least 500,000 acres.

Another comparison puts this into sharper perspective: Today there are about 11 acres of high quality farmland in the Valley for every acre of urbanized land. By mid-century, there will be less than five – unless we do something different. (Unger and Thompson, 23)

AT THE PROJECT LEVEL

“Every square foot of space built through internal densification decreases the amount of space needed in the form of sprawl” is how I synopsized infill vs edge development in 2009. My statement reflects the occupied space displacement[i]. But there is more.

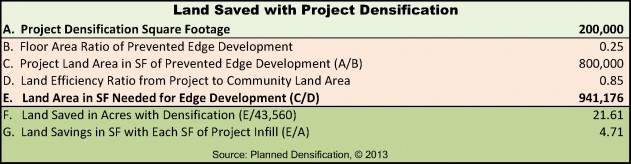

Because of the low density at the edge, a tremendous amount of land is required relative to the square footage of buildings. In addition, infrastructure and civic space to service the land area are spread out more. For perspective, here are calculations of the land ‘savings’ that are realized by producing 200,000 square feet as project densification instead of edge development, the amount that might be added to a neighborhood or community shopping center as demand in a local market evolves. This scenario might represent improving a 200,000 square foot project from .25 to .50 FAR.

So, how much farm land does project densification save? One Square foot of densified project space can save about five square feet of edge land (see table). The total land savings is 941,177, or 21.61 acres with suburban project assumptions of a .25 FAR and .15 factor for roadways and other civic space. I use the term savings because project densification requires no new land, and less per square foot infrastructure than new edge development.

To put this another way, for about every 9,250 square feet of project infill, one acre of edge development might be eliminated, and one acre of farmland saved (43,560/4.71).

REGIONAL PERSPECTIVE

Growth is important. And achieving a mix of low- and high-density neighborhoods is crucial in order to satisfy demand from the variety of residential and commercial occupancy needs now present, as well as to provide land use patterns and mixes that are fiscally more productive. As it is, most development in the San Joaquin Valley is low density without pre enablement for coevolving with market demand in key locations–meaning that it will likely remain low density.

Though the excessive suburban development occurs over many years, today’s context suggests urgency. Numerous planning studies and updates to regulatory documents are occurring in the San Joaquin Valley. Implementation of these new guidelines and regulations will shape the next generation of urban development and its impact on citizens, municipal finances, and the regional economy. To improve outcomes, it is essential to look beyond desired land development patterns and address the project level feasibilities, as well as how project feasibilities relate to market evolution and life cycles. When these additional factors are considered, it is clear that we must pre enable densification in key locations.

This scenario of excessive low density development at the urban edge, often on agricultural land, occurs across the Nation but is fairly summarized by the American Farmland Trust report for the San Joaquin Valley

No sector of the Valley’s economy has a greater stake in how– and where – communities grow than agriculture. Land is the foundation of farming and ranching, and every acre of agricultural land converted to urban use is an acre that will never again sustain food production. It is also an acre that will no longer yield benefits of nature such as wildlife habitat, groundwater recharge or the beauty of a peach orchard in full bloom.

Though it may seem like there is plenty of farmland in the San Joaquin Valley, it is, in fact, a finite resource. And demands on that land continue to grow, not only for urban development but, just as importantly, to feed a growing population, provide renewable energy, and safeguard the environment. Conserving this irreplaceable resource –saving farmland while growing our cities – is an imperative for truly sustainable planning in the years to come. (Unger and Thompson, 2)

[i] A one-to-one displacement is probably an underestimation because many building occupants utilize more space on the edge than they would in interior locations, in part because space is cheaper; indeed, this better value for space is an important input into location selection for households and businesses. Infrastructure cost and operation are higher, and municipal revenue lower per unit of measure on the suburban edge.

Citation

Unger, Serena and Edward Thompson, Jr. Saving Farmland, Growing Cities, A Framework for Implementing Effective Farmland Conservation Policies in the San Joaquin Valley. (Davis: American Farmland Trust, 2013).

Addendum–Photographs of low density urbanization on the edge of Modesto, CA. Images from Microsoft/Bing/Nokia.